Fetal Personhood before Roe v. Wade

The beginnings of an all-or-nothing movement

This is the second part in a series covering the Fetal Personhood ideology.

Read part 1 here.

A new rhetorical strategy

As states began to ease abortion bans in the 1960s, at the same time as the Civil Rights Movement was making headway in the courts and in the public conscience, opponents of contraception and abortion shifted their anti-abortion strategy, believing that “by moving away from” predominantly Catholic “religious arguments, [they] could attract a broader, more diverse following.”1 These activists’ new strategy was to “borrow[] the rhetoric of civil rights” and put this rhetoric “to conservative ends.”2

The activists “who repurposed the language of civil rights in this movement were almost all white.”3 While “some might have… considered themselves liberals,”4 the 1960s anti-abortion movement was never a liberal movement when it came to women.5

“Sexual moralism was never ancillary to this movement, nor was anti-feminism an afterthought.”6 “Sexual moralism was in the movement's political blood from the very beginning.”7

These activists “were influenced by sexually conservative movements like the anti-birth control and anti-pornography movements, much more than anti-poverty or civil rights movements. They may have been interested in the poor and the disenfranchised but those interests were not what motivated their anti-abortion activism. It was in the anti-porn and anti-birth control movements where they formed the intellectual frameworks that would later translate into anti-abortion politics. Even if some activists had been New Deal Democrats, they were always sexually conservative ones,”8 and they “were drawn from similar demographics as other mid- to late-twentieth-century conservatives.”9

Furthermore, “while linking their fight to the civil rights movement, very few abortion foes actually campaigned for equal treatment for people of color.”10 “Indeed, antiabortion leaders maintained that abortion was worse than slavery or the Holocaust” and “positioned fetuses, many of them white, as the ultimate victims of discrimination in the United States.”11 Nevertheless, anti-abortion activists recognized that their movement could benefit from appropriating the language of Civil Rights.

While “the white men and women of this movement claimed that theirs was a civil rights movement,”12 in reality, through the appropriation of Civil Rights rhetoric, “older visions of moral degradation” were often merely “transformed into more modern conceptions of rights abuses.”13 Through language, activists were strategically “riding a… modern political wave.”14 “They borrowed… from the black civil rights movement and the international human rights movement when framing their story. But make no mistake: This language was always in service of denying others their rights.”15

Prior to this period of abortion ban liberalization and repeal, “more than one-third of states criminalized the actions of women who terminated their own pregnancies or asked others to do so.”16 In practice, however, “few women went to prison for having an abortion, although many faced embarrassment and stigma during the very public prosecution of doctors or lovers.”17 Women who refused to testify against their doctors did face the possibility of being prosecuted for contempt of court, even in states where women could not be prosecuted for abortion.18

By the early 1970s, “over a dozen states had passed” legislation liberalizing abortion bans, “and a handful [of states] repealed all criminal abortion restrictions.”19 While working to counter this liberalizing wave, anti-abortion activists “rarely discussed the punishment of women.”20

Strategically, “by focusing on the fetus, [anti-abortion] activists could sidestep the fraught issue of women's rights in an era when feminist values were infusing popular culture and politics.”21 Yet anti-abortion activists were always deeply uncomfortable with and concerned by “changing sexual mores and the status of women in society.”22 “[A]ctivists realized that an anti-woman's rights platform would not help them win the day. Facing the rising tide of feminism, anti-abortion activists chose not to attack women directly but instead focus attention on the rights of the ‘unborn.’”23 Nevertheless, Fetal Personhood and the punishment of pregnant people are inextricably linked, as the decision in Roe v. Wade would later elucidate.

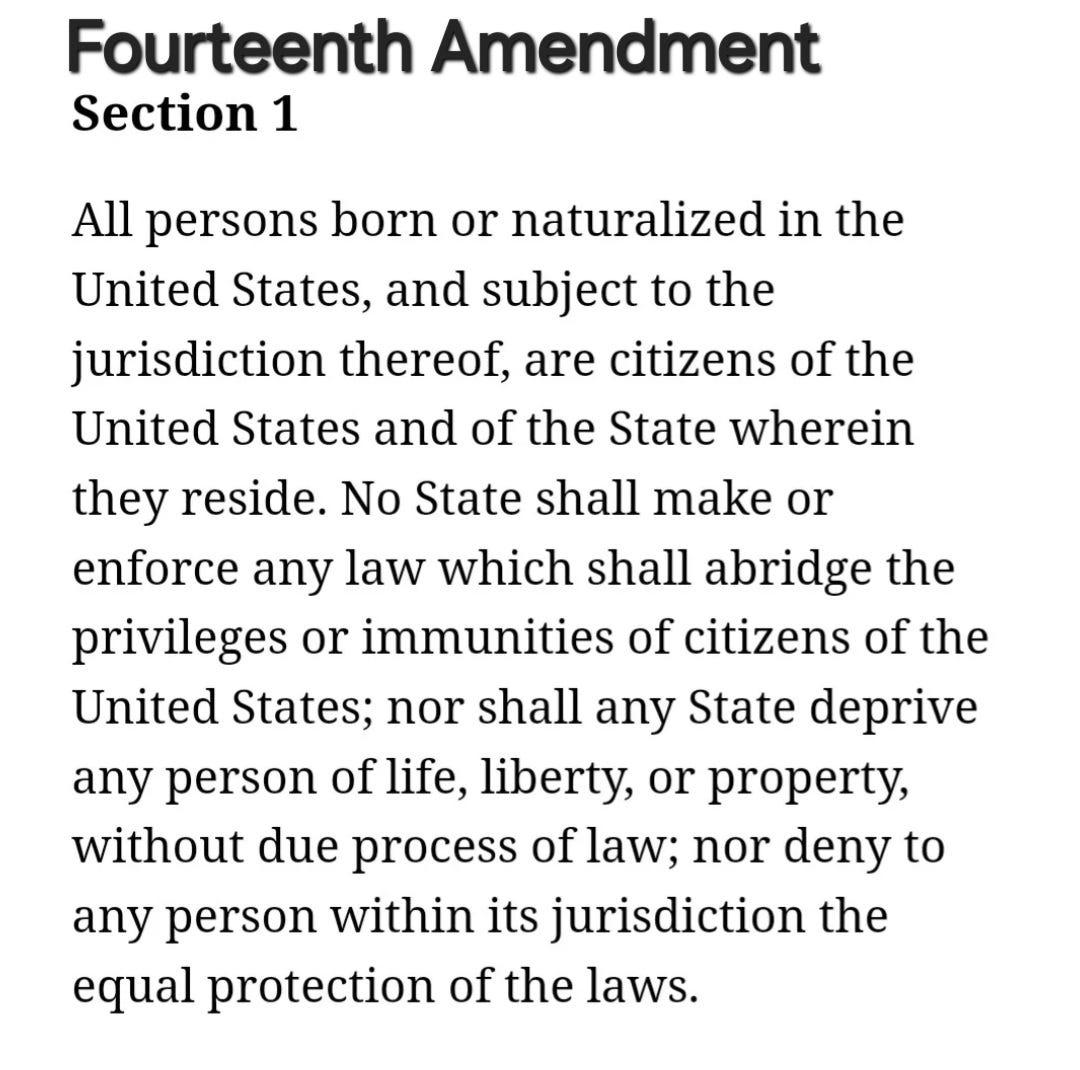

For the time being, however, anti-abortion activists in the 1960s chose fetal-centric arguments, specially focusing on Fetal Personhood and the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.24

Fetal Personhood and the Fourteenth Amendment

“Starting with its landmark school desegregation decision, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the [Supreme] Court had shown new solicitude for marginalized minorities, especially Black Americans, and under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, it had begun to closely scrutinize any law that classified people by race.”25 Taking their cue from this decision, anti-abortion activists in the late 1960s “forged [their] own court-centered strategy.”26 Activists began to argue that fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses were “persons” under the Fourteenth Amendment. With this argument, “leaders of the anti-abortion movement believed the Court might see the unborn as another embattled minority.”27

While a few anti-abortion lawyers did make the argument that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment had intended to include fertilized eggs, embryos, and fetuses as persons, “for the most part, the [anti-abortion] movement argued that the meaning of the 14th Amendment changed over time. While the ‘original intent’ of the 14th Amendment had been to stamp out racism,” wrote anti-abortion scholar Robert Byrn, “the meaning of the amendment had changed, and now, its protections applied before birth as well as afterward.”28

Some anti-abortion lawyers began to “argue[] that before an abortion could constitutionally take place, a judge would have to appoint a guardian to speak on behalf of an unborn child and hold a hearing.”29 David Louisell, a conservative from Minnesota, was among those who hoped to argue that embryos and fetuses “counted as rights-holding persons under the Fourteenth Amendment.”30 “Appointment of a guardian [ad litem] to represent the fetus,” Louisell wrote, “would seem feasible and would be the minimum starting point for any attempt at due process.”31

In the 1973 Supreme Court case, Roe v. Wade, Texas argued that embryos and fetuses are persons under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court's decision in this case would jumpstart the Fetal Personhood movement as we know it today and, according to anti-abortion activists, would “set[] the table for” establishing Fetal Personhood in the future.32

In the next post we'll look at the decision in Roe v. Wade and the tactics of the post-Roe Fetal Personhood movement.

Ziegler , M. (2022). Controlling the Court . In Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment (p. 51). essay, Yale University Press.

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 17). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 17). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 35). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 35). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 35). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 35). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 35). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 17). essay, University of California Press .

Ziegler , M. (2022b). The reform battle and the right to privacy . In Reproduction and the Constitution in the United States (p. 52). essay, Routledge.

Ziegler , M. (2022b). The reform battle and the right to privacy . In Reproduction and the Constitution in the United States (p. 52). essay, Routledge.

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 19). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 19). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 19). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 19). essay, University of California Press .

Ziegler, M. (2018). Some form of punishment: Penalizing women for abortion (p. 744). William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol26/iss3/6/

Ziegler, M. (2018). Some form of punishment: Penalizing women for abortion (p. 740). William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol26/iss3/6/

Ziegler, M. (2018). Some form of punishment: Penalizing women for abortion (p. 746). William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol26/iss3/6/

Ziegler, M. (2018). Some form of punishment: Penalizing women for abortion (p. 746). William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol26/iss3/6/

Ziegler, M. (2018). Some form of punishment: Penalizing women for abortion (p. 746). William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol26/iss3/6/

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 19). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 19). essay, University of California Press .

Holland, J. L. (2020). Introduction . In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (p. 19). essay, University of California Press .

Ziegler, M. (2018). Some form of punishment: Penalizing women for abortion (p. 747). William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol26/iss3/6/

Ziegler , M. (2022). The Fall of Personhood. In Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment (p. 32). essay, Yale University Press.

Ziegler , M. (2022). The Fall of Personhood. In Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment (p. 32). essay, Yale University Press.

Ziegler , M. (2022). The Fall of Personhood. In Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment (p. 33). essay, Yale University Press.

Ziegler, M. (2024, March 24). The endgame in the battle over abortion - politico. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2024/03/24/personhood-abortion-legal-fight-00147138

Ziegler , M. (2022b). The reform battle and the right to privacy . In Reproduction and the Constitution in the United States (p. 51). essay, Routledge.

Ziegler , M. (2022). The Fall of Personhood. In Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment (p. 33). essay, Yale University Press.

Ziegler , M. (2022). The Fall of Personhood. In Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment (p. 33). essay, Yale University Press.

Clemons, D. (2012, January 31). Personhood movement comes to Alabama. Journal. https://times-journal.com/news/article_10480dca-493a-11e1-8fe7-001871e3ce6c.html