What are hormonal contraceptives and how do they prevent pregnancy?

A Guide to Hormonal Contraceptives

Contents and Outline

What are hormonal contraceptives?

“Contraception is the act of preventing pregnancy. This can be a device, a medication, a procedure or a behavior.”1 There are both hormonal and non-hormonal methods of contraception. This guide focuses specifically on hormonal contraception.

Hormonal contraceptives (HCs) are a method of contraception that acts on the endocrine system (the body's “messenger” system) through the use of hormones to prevent pregnancy.2 Hormonal contraceptives may contain both estrogen and progestin, or may only contain progestin.3 Hormonal contraceptives come in a variety of forms: pills, intrauterine devices (IUDs), patches, injections, vaginal rings, and implants.

Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) are a category of hormonal contraceptives (HCs) “that contain both an estrogen and a progestin component” (emphasis added).4 The estrogen is added “to provide better cycle control,”5 though estrogen also contributes to ovulation suppression.6 “In today's CHCs, the estrogen component is most often EE (ethinyl estradiol), whereas there are many different types of progestins used.”7

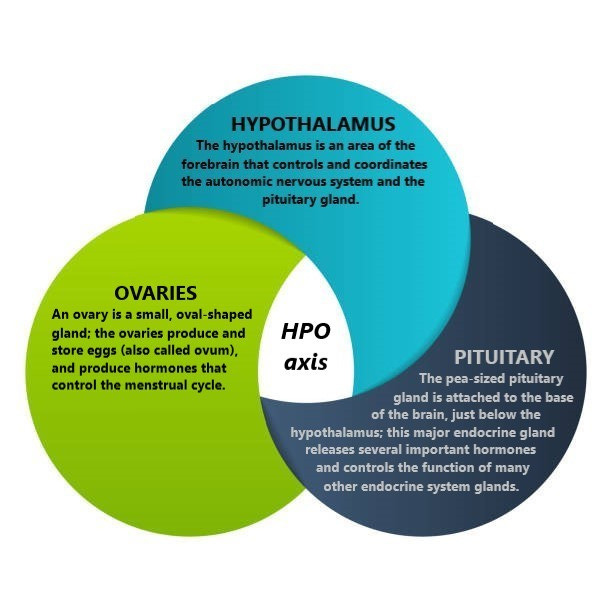

The progestin component of both HCs and CHCs “provides the main contraceptive effect.”8 To understand how the progestin component of hormonal contraceptives works to prevent pregnancy, one must first understand the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis

“The menstrual cycle is controlled by a multitiered system, which involves both the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and the ovarian-endometrial compartment.”9 For the purposes of this discussion, we will be focusing only on the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis. It is the HPO axis that “is responsible for hormonal cycling - producing the right amount of sex steroids at the right times in the cycle to… mature the oocyte (immature egg) for ovulation,” trigger ovulation, and “create the right conditions for fertilization to take place.”10

In this system, signals travel “from the hypothalamus to the pituitary, and then from the pituitary to the ovary.”11

■ HPO axis and ovulation

The hypothalamus and the pituitary gland “assess various aspects of ovarian activity by monitoring circulating levels of sex steroids (estrogen and progesterone) and other hormones” that are produced by the ovaries;12 and, importantly, no activity in the ovaries is possible without the “stimulation from [these] higher centers” of the HPO axis (the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland).13

The hypothalamus uses “pulses”1415 to control the pituitary gland’s “production and release of two different” hormones “in different amounts at different times in the [menstrual] cycle to regulate the activities of the ovary, including ovarian hormone production.”16 These two important hormones produced by the pituitary gland are called the follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and the luteinizing hormone (LH).17

By detecting ovarian activity, the hypothalamus determines “how much stimulation” is needed “to produce the right [pulsatile] signals to send to the” pituitary gland.18

The pituitary gland then determines how much hormones to secrete.19 The follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and the luteinizing hormone (LH) secreted by the pituitary gland are then “carried in the bloodstream to the ovaries, where they stimulate the production of sex steroids and other hormonal proteins needed to enable ovulation.”20

Hence, “ovulation begins when the female brain releases specific hormones that spike in the bloodstream, triggering the release of an egg.”21

■ HPO axis and fertilization

In addition to ovulation, the HPO axis is also vital to the creation of conditions which enable fertilization to take place.22

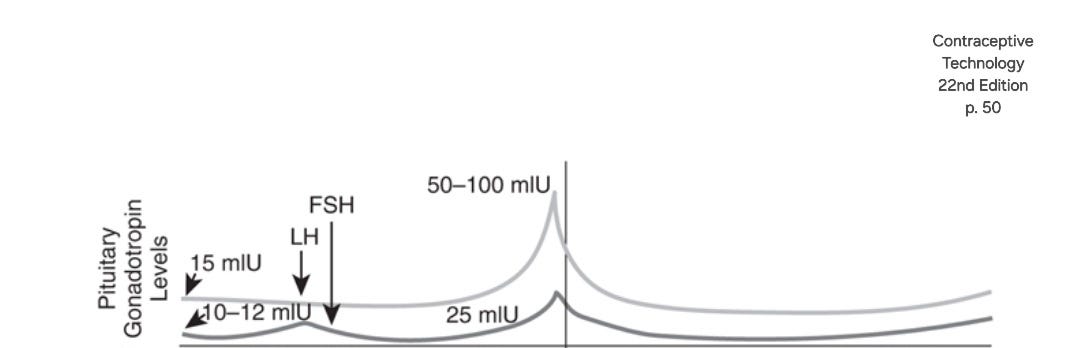

In the preovulatory period, the maturing egg follicle will release large amounts of estrogen.23 “[T]he high levels of estrogen from the ovaries,” coupled with “very modest levels of progesterone,” will “prompt the hypothalamus and pituitary to secrete more FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) and LH (luteinizing hormone) to induce ovarian production of even more estrogen.”24 It's this increase in ovarian estrogen production, caused by the surge of FSH and LH, that creates “the right conditions for fertilization to take place.”25

The diagram below shows the surge in the levels of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) that occurs just before ovulation.26 The center vertical line marks the point of ovulation, occurring just after the peak FSH/LH surge. (*Note: “Ovulation occurs approximately 30 to 36 hours after the start of the LH surge and about 10 to 12 hours after the LH peak.”)27

As noted above, the increase in estrogen production in the ovaries that is prompted by the surge in follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) that occurs just before ovulation, is what creates “the right conditions for fertilization to take place.”28 In the following ways, “the high levels of estrogen in the preovulatory period are critical” for fertilization to occur.29

🟢 High levels of estrogen are needed to change cervical mucus. “For most of the cycle, cervical mucus is thick, tenacious, and impenetrable; it blocks entry of the sperm [] into the upper genital track. However, in the face of high levels of estrogen,” the thickness and stickiness of the cervical mucus decreases dramatically.30 “Profuse, watery mucus protrudes from the cervix into the vagina… This mucus has channels that are slightly wider than a sperm head to provide the sperm safe harbor from the acidity of the vagina and an entry pathway for the sperm… A characteristic ferning pattern can be seen microscopically on slides after this estrogenized mucus has dried.”31

🟢 “High levels of estrogen also reverse the direction of uterine contractions. During most of the cycle, the uterus spontaneously contracts from the fundus,” the upper, widest area of the uterus, “toward the cervix,” the lower, most narrow part of the uterus, “to expel its contents.”32 However, “during the LH surge, the contractions start from the cervix and propagate upward to the fundus, creating a current to help the sperm propel through the cervix into the endometrium and toward the ostia (mouth) of the fallopian tubes.”33

🟢 “Estrogen is necessary for the cilia (hairlike structures) in the fallopian tubes to maintain their secretory activity and to increase the spontaneous muscle contractions along the tubes. Both of these changes are needed to support the sperm and to push them toward the egg for fertilization.”34

Understanding the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and its role in ovulation and fertilization, we can now examine how hormonal contraceptives work to prevent pregnancy.

How do hormonal contraceptives prevent pregnancy?

In short, hormonal contraceptives (HCs) “disrupt the feedback system between the brain and ovaries, thus inhibiting the release of an egg,”35 as well as depriving sperm of the environmental conditions necessary for sperm and egg to meet.

As noted in the first section of this guide, the progestin component of both HCs and CHCs “provides the main contraceptive effect”36 (though estrogen also contributes to ovulation suppression).37 “By providing high levels of progestin throughout the cycle, hormonal contraceptives (with or without estrogen)” interact with the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, and thus interfere with ovulation and fertilization in the following ways.38

🟢 “Progestins block the changes that estrogen has on cervical mucus mid-cycle. Consequently, the cervical mucus remains thick and impenetrable to the sperm at all times in the cycle, even if an LH surge occurs.”39

🟢 “Progestins keep the uterine contractions moving from the fundus to the cervix, which reduces the number of sperm that enter the upper track.”40

🟢 “Progestins thin the tubal epithelium and slow the ciliary action needed for fertilization” to occur,41 “decreaseing[] tubal motility by reducing activity of the cilia in the fallopian tube, which prevents the sperm and the egg from meeting.”42

🟢 Progestins “alter[] luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion, resulting in inhibition of ovulation.”43

By disrupting the signals and communication within the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, hormonal contraceptives inhibit ovulation and deprive sperm of the environmental conditions necessary for sperm and egg to meet (fertilization). Hormonal contraception is a safe and effective method of preventing pregnancy.

🌟 To learn more about the mechanism of action of various hormonal contraceptive methods, see “Mechanisms of action: The pill, the implant, the shot, and IUDs.”

Bansode OM, Sarao MS, Cooper DB. Contraception. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536949/

NCI Dictionary of Cancer terms. Comprehensive Cancer Information - NCI. (n.d.). https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/hormonal-contraception

NCI Dictionary of Cancer terms. Comprehensive Cancer Information - NCI. (n.d.). https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/hormonal-contraception

Ramanadhan, S., & Edelman, A. (2025). Combined Hormonal Contraceptives (CHCs). In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 401). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Ramanadhan, S., & Edelman, A. (2025). Combined Hormonal Contraceptives (CHCs). In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 403). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Ramanadhan, S., & Edelman, A. (2025). Combined Hormonal Contraceptives (CHCs). In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 403). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Ramanadhan, S., & Edelman, A. (2025). Combined Hormonal Contraceptives (CHCs). In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 403). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Ramanadhan, S., & Edelman, A. (2025). Combined Hormonal Contraceptives (CHCs). In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 403). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 53). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Frank, Rachel. “Miss-Conceptions: Abortifacients, Regulatory Failure, and Political Opportunity.” Yale Law Journal, vol. 129, no. 1, Oct. 2019, pp. 215. 2019-2020, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/pdf/FrankNote_nsp64s9w.pdf

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 59). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 59). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 62). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 50). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 60). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 60). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 60). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 60). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 60). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 60). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Frank, Rachel. “Miss-Conceptions: Abortifacients, Regulatory Failure, and Political Opportunity.” Yale Law Journal, vol. 129, no. 1, Oct. 2019, pp. 215. 2019-2020, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/pdf/FrankNote_nsp64s9w.pdf

Ramanadhan, S., & Edelman, A. (2025). Combined Hormonal Contraceptives (CHCs). In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 403). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Ramanadhan, S., & Edelman, A. (2025). Combined Hormonal Contraceptives (CHCs). In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 403). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 61). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 61). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 61). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Nelson, A. L. (2023). Understanding the Physiology of the Menstrual Cycle. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 61). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Roque, C. L., & Burke, A. E. (2025). Progestin-only Pills. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 462). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Roque, C. L., & Burke, A. E. (2025). Progestin-only Pills. In Contraceptive Technology (22nd ed., p. 462). essay, Jones & Bartlett Learning.